Cued Speech

The following information is excerpted from a blog that I wrote for DeafDC.com in 2007. You can download the original here: Cued Speech: Your Unasked Questions Answered [PDF]. Please note: This column is copyrighted and you may not distribute excerpts or the blog it in its entirety without appropriate reference to the author (Hilary Franklin) and DeafDC.com.

Just what is Cued Speech, anyway?

Good question! Cued Speech is not a language. Cued Speech is not a tool for teaching speech. Cued Speech is a mode of communication that allows a person to express and understand a traditionally spoken language visually, through cues.

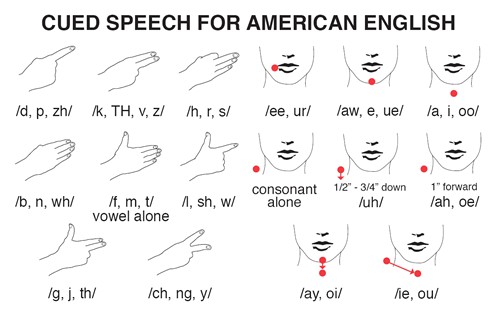

More formally, Cued Speech is the name of the visual-manual system/code that Dr. Orin Cornett developed in 1965-1966 while working at Gallaudet College. For English, the system comprises eight handshapes that represent consonant phonemes and four hand placements and two movements that represent vowel phonemes. Consonants that have similar mouth shapes are assigned to different handshape groups. Likewise, vowels that look alike are assigned to different hand placement/movement groups.

For example:

/m/ /b/ /p/

They all have the same mouth shape, right?/mat/ /met/ /bat/ /bet/ /pat/ /pet/

Oy vey! Unless you’re an elite lipreader, how can you tell the difference between these words?

- The handshape for /m/ is similar to the open B handshape in ASL.

- The handshape for /b/ is the same as the B handshape in ASL.

- The handshape for /p/ is the same as the 1 handshape in ASL.

- The handshape for /t/ is the same as the handshape for /m/ (/t/ looks very different on the lips than /m/)

- The vowel location for /e/ is at the center of the chin.

- The vowel location for /a/ is at the base of the throat (just above the sternum notch, and below the Adam’s apple).

By combining the handshapes, the hand placements/movements, and the mouth shapes (no voice required), the distinction between look-alike mouth shapes is made completely clear. Cues are strung together, just like consonants and vowels are strung together. A single cue comprises a consonant-vowel combination.

For example: The word tea is one cue: /tee/, whereas the word tiki is two cues: /tee/ + /kee/.

For words that have “null” vowels or consonants like meet, which has no vowel after the /t/, a rule exists to cue the /t/ in a “neutral” location, which shows that it is a /t/ without a vowel after it. Likewise, vowels have a neutral handshape that indicates it is produced alone or at the beginning of a new word or syllable (like eye or e-mail).

Therefore, cueing provides immediate access to consonant-vowel languages that are traditionally spoken. With all the phonemic information visible on the lips and hands, we can cue strings of consonant-vowel combinations, just as if we were speaking them. We can cue various everyday words, nonsense “words” like supercalifragilisticexpialidocious or oompa loompa, or foreign words such as gracias and auf wiedersehen. We can even cue the current longest word in the English dictionary: antidisestablishmentarianism.

Now, a major reason for the confusion about what Cued Speech is results from the second word in the name of the system, “speech.” Dr. Cornett was a physicist and mathematician, not a linguist or speech therapist, and liked to solve logic puzzles. Additionally, Cued Speech was developed in the mid-1960s, when many people thought that phonics and speech and language were intimately linked and could not be separated. We now know that’s not true. It is possible to have phonemic awareness without speaking. I know quite a few cuers who do not use their voices. Therefore, the name “Cued Speech” was perfectly agreeable at that time. The name of the system has been, and will continue to be known as Cued Speech. It’s not going to change.

Cued Speech ≠ Speech

While it is possible to cue speech sounds individually, simply cueing alone cannot and will not improve any deaf person’s speech. What it can do is provide visual biofeedback to a deaf or hard of hearing (or hearing second language learner) who is struggling with a target sound. For example, if you’re trying to say /k/ but it sounds like /g/, the speech therapist will cue to you what sound you are actually producing. There is nothing in the cues that tells you that the back of the tongue must be raised to the roof of the mouth and then brought down, without any vocal cord movement, to create the sound /k/. The responsibility of teaching speech still belongs to the speech therapists, parents, and anyone involved with the speech training of the deaf child.

Pronunciation can be corrected though, provided the deaf cuer has the ability to produce the speech sounds. For example, when I was about eight years old, I saw a Home Depot and turned to my mother and said, “oh, look, home dee-POT!” She laughed and cued, “no, it’s home dee-PO.” I became cranky and complained about the silent “t” at the end of the word. She explained to me that the word is French and that we “borrow” the French pronunciation of their words. So while she could correct my pronunciation of the word depot, she did not teach me how to say the individual sounds in that word—my speech therapists did.

Language & Communication (in English)

Languages are expressed in different ways: they can be spoken, written, or signed. They can also be cued. Speaking is a mode. Writing is a mode. Signing is a mode. Cueing is a mode. When we think of English, we typically think of spoken English or written English (and sometimes signed English). We don’t think about cued English as often, but it happens every day. Of these modes, only speaking and cueing are the most parallel. The written form of English does not always jibe with the spoken form. For example, cheer and fear sound the same, but fear and bear do not. And then bear and bare are exactly alike! Good grief! However, each of those words are cued comparatively to the spoken form, not to the written form. This means that residual hearing is not necessary to understand cued English. The system is entirely visual.

Manually Coded English Systems

Signed English and other manually coded English (MCE) sign systems do not accurately portray the properties of the English language. While you can sign CAT + S to represent the idea of “more than one cat,” the sign for CAT has no inherent relationship to /k, a, t/. It is one of the few “iconic” signs that represents a physical feature of the object/person; in this case, cats or gatos. The same is true for any sign – I don’t know of any signs that represent the phonemic properties of English words. The created endings (-S, -ING, -ED, etc.) show the spelling, and even the movement for “-ING” typically doesn’t show the individual fingerspelled letters I-N-G.

And then add to the mix the MCE systems that try to break down compound words. For example, the word butterfly in Seeing Essential English is broken down into the signs for butter and fly. In other words, the person would sign BUTTER and then sign FLY. Somehow, I just really don’t want to associate butter and planes with butterflies.

Cued Language/cued English

Because we are cueing the basic elements of consonant-vowel languages, we refer to cued communication as cued language. Thus, children who are exposed to English or other spoken languages through cueing have direct access to the consonant-vowel structure and grammar rules and can begin developing a mental understanding of English (or Spanish, French, Hebrew, Hindi, etc.), even if they never hear the sounds or speak them. In the United States, deaf cuers communicate in cued English.

Deaf cuers (and hearing cuers) who have fluent/proficient expressive and receptive abilities communicate with one another as naturally as hearing individuals talk to each other or signing people with each other. While the deaf cueing community here in the United States is admittedly relatively small (compared to the signing and oral communities), believe me, when we get together, many of us enjoy being able to communicate in our native mode!

Cued language transliterating

Unlike ASL interpreters, cued language transliterators convey the exact message being said and in the same language, just in a different mode – spoken English to cued English or vice versa. If I’m in a biology class and the professor is talking about the process of mitosis, the transliterator doesn’t need to understand what mitosis is or have to worry about making sure the concept is conveyed accurately. As a student, that’s my job – to understand what the professor is saying. And seeing as how I know next to nothing about mitosis:

“Mitosis is nuclear division plus cytokinesis, and produces two identical daughter cells during prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase.”

All the transliterator has to do is cue:

/mie, toe, si, s, i, z, nue, k, lee, r, di, vi, zhuh, n, p, luh, s, sie, toe, ki, ne, si, s ……/

You get the idea. It’s just consonants and vowels strung together. Easy work for the transliterator. Not so easy for someone trying to interpret that into ASL.

Cued Speech and American Sign Language

What I’m about to say here is a fairly radical idea and one that is just beginning to be discussed in various circles. With the growing interest in bilingual-bicultural education, the importance of stressing proficiency in English and ASL is even more paramount. For so long, deaf education professionals, parents, and deaf individuals themselves have struggled to provide deaf children with clear access to English. Teaching English via cueing provides that answer. Cueing is direct and visually conveys the elements of English at the most basic, necessary language foundation level to anyone, deaf or hearing. Signing is direct and visually conveys the most basic, necessary foundation of American Sign Language to anyone, deaf or hearing.

Signing is a mode that should be used exclusively for signed languages. Cueing is a mode that should be used exclusively for cued/spoken languages. No longer would signs and fingerspelling need to be used for English words or in English order. With access to appropriate ASL and cued English language models, children could be immersed in both languages through entirely visual-manual means, and separately from one another. We have all seen the influence of English language order signs on ASL. With both ASL and MCE systems using signs as the mode of communication, it is inevitable that teaching English through signs will affect a person’s ASL proficiency and perhaps understanding of the English language itself. Thus, by cueing in English and signing in ASL, you will be ensuring and encouraging the appropriate use and development of each language.

The importance of visual, clear access to English in the home

There is also the issue of deaf children needing appropriate access to language at home. We all know that the majority of parents are hearing and do not sign fluent ASL. We cannot reasonably expect these parents to become fluent signers and appropriate ASL models overnight. Learning a new language takes as much as two years or more, even with full immersion. A deaf child born into a hearing family that does not provide visual, appropriate, and complete access to the language environment will have a language delay by the time s/he enters formal schooling.

Because Cued Speech is a finite system based upon the consonant-vowel properties of English (and other spoken languages), it is possible for parents and other family members to learn to cue in just a few hours, usually over the course of a two-day workshop. Rather than learning a new language, they are learning a new code for a language they already know. They leave the workshops cueing accurately, but slowly. With practice, speed and fluency come, but they can start cueing anything they say to their child. Thus, parents become appropriate models of English to their deaf child(ren), and immediately. I also encourage parents to expose their children to deaf signers who are appropriate ASL models. In this way, the children have access to the family’s home language AND to American Sign Language, not some creolian mix of PSE or signing/lipreading combinations, etc.

Deaf Cuers and Identity

Again, the d/Deaf cueing community is a small subset of the large d/Deaf community in the United States. Not all cuers learn how to sign. Many do, and for various reasons. I won’t dare represent anyone else but me. I grew up in the DC area and therefore have interacted with signers since I was in elementary school. It was necessary for me to learn how to sign fluently to interact with other deaf peers in middle school and high school, and I embraced it eagerly. If I had attended a school where I was the only deaf student and in a location where access to the signing deaf community was limited, I might not be signing today.

With regard to identity, I have always identified myself as a person who is deaf. I also identify as a native cuer and near-native signer. In some blogs, I’ve seen people suggest or imply that because not all deaf cuers are obviously “out” as cuers that they’re ashamed of having grown up cueing. I will tell you that my personal experiences and various discussions with my fellow cueing friends present a completely different view. I don’t think any of us are ashamed about cueing, and we would gladly talk about it – it’s just that many times, Cued Speech doesn’t come up in conversation. Or, when it is brought up, sometimes the attitude of the other person is negative and it’s better to handle that kind of situation privately than in public. Also, sometimes the cuer’s background just isn’t relevant to the topic or situation at hand. For example, if you and I are having a discussion about international politics, why would I mention Cued Speech or that I’m a native cuer?

###

Reminder: You can download the PDF of the original here: Cued Speech: Your Unasked Questions Answered [PDF]